Introduction

According to the Firth Assessment Report (AR5) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), temperature in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is projected (RCP 4.5 scenario) to rise by about 1.5–2.5 °C by 2050 (IPCC et al., 2014). In terms of observed trends, SSA has witnessed a 0.2–2.0 °C increase in temperature (IPCC, 2007). Across the rest of Africa, there are observations of increase near surface temperature of about 0.5 °C during the last 50–100 years (Niang et al., 2014; New et al., 2016). Regionally, North Africa has witnessed annual and seasonal observed increasing trends in mean surface temperature that are significantly beyond the rates and ranges of changes caused by natural variability. West Africa and Southern Africa on the other hand also witnessed increased near surface air temperature over the last 50 years (IPCC, 2007). In the context of temperature projections, it has been projected that temperature in Africa will rise faster than what has been projected at the global scale during the 21st century. Near surface air temperature in Africa are projected to be beyond the 20th century projection by 2069 (±18 years) under the RCP4.5 scenario and by 2047 (±14 years) under the RCP8.5 scenario (IPCC, 2007; James and Washington, 2013; New et al., 2016). These changes will be unprecedented in more vulnerable regions like West, Middle and East Africa (Epule et al., 2021a) as projections of increase temperature are likely to occur 1-2 decades earlier than expected (IPCC, 2007).

As concerns precipitation, North Africa has shown a strong decrease in the amount of precipitation during winter and spring. Trends show greater than 330 dry days with less than 1 mm of precipitation per day for the period 1997–2008 (IPCC, 2007; IPCC et al., 2014). West Africa and the Sahel also witnessed average reduction in precipitation during the first half of the 20th century due mainly to natural variability and an increase in precipitation from the mid 1980s due mainly to increase greening and aerial fertilization effects of carbon dioxide (Biasutti and Giannini, 2006; Greene et al., 2009; IPCC et al., 2014). East Africa on the other hand witnessed a decease in precipitation over 30 years while Southern Africa witnessed a reduction of precipitation in late summer from the western part extending to Namibia, through Angola during the second half of the 20th century (IPCC, 2007; IPCC et al., 2014). Projections of precipitation show that future precipitation is uncertain. Indeed, CIMIP5 ensemble models project decease in mean annual precipitation across the Mediterranean region of North Africa in the mid and late 21st century based on the RCP8.5 scenario (IPCC, 2007; IPCC et al., 2014). CIMIP5 further projects a decease in mean precipitation over Southern Africa beginning from the mid to late 21st century and based on the RCP8.5 scenario (IPCC, 2007; IPCC et al., 2014). According to CMIP3 and CIMIP5 projections, West African is likely to witness a wetter core rainy season; similar projections are held for most of East and Middle Africa with increase precipitation projected from the mid 21st century as per the RCP8.5 scenario (IPCC, 2007; IPCC et al., 2014).

The effects of the above observations and projections in precipitation and temperature across Africa are already having daunting impacts in Africa. Africa is particularly vulnerable because it is essentially dependent on rainfed agriculture, and its populations are not adequately adapted (Collier et al., 2008). The continent is already witnessing rife rates of droughts, floods, and resultant damages to crops and property (Toulmin, 2009). In response to this, governments, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), International organizations, inter alia are ramping up efforts to enhance policy efforts in attempts at grappling with the negative effects of climate change (Simelton et al., 2009; Epule et al., 2017a). Many of the initiatives that have been put in place to adapt and mitigate the challenges imposed by climate change involve, technologically based options, indigenous based options, and socio-economically based options (O’Connor and Ford, 2014; Epule et al., 2017b).

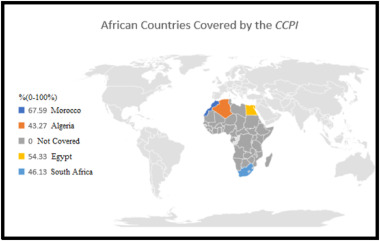

Now, it is important to be able to assess how different parts of Africa are performing in the context of climate change policy. This is important because it will provide a baseline against which we can evaluate, assess, and monitor how different countries and regions are performing in the context of climate change policy. To achieve this, new approaches, methods, and data that assesses climate change policy performance across Africa must be developed. This is particularly important for Africa as the continent is highly vulnerable to climate change (Epule et al., 2017a; Epule, 2021). The first global effort to evaluate climate change policy performance around the world was based on the Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI). The CCPI was developed in 2005 by the German Watch Institute and has since then reported and updated climate change policy performance around the world (Burck et al., 2009). The CCPI focuses on four key variables which are: greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy, energy use and climate policy. It focuses on 57 countries of the world which represent 90% of global greenhouse gas emissions (Burck et al. 2019). Unfortunately, the CCPI only covers four countries in Africa, which are: Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, and South Africa (Fig. 1) (Burck, 2009; Burck et al. 2019).

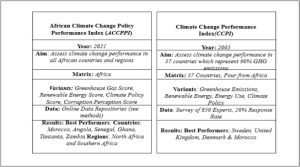

As a result, this current study aims at filling this huge research gap by developing a first of its kind Climate Change Policy Performance Index that is feasible to African realities and adaptable in other parts of the world. Also, the ACCPPI is rationalized by other weaknesses of the CCPI which include: Failure to quantify and include a measure or a proxy for corruption which is a key performance indicator in many developing regions including Africa. Also, the CCPI uses renewable energies and energy efficiency which have been described as overlapping and leading to co-linearity. The latter has been described as a major weakness of CCPI that warrants new approaches; a weakness this current work avoids. Furthermore, the approach used by the CCPI is based on online questionnaires which only had a 20% response rate. Following difficulties associated with administering such online surveys in Africa as well as issues of coverage and representation, this current ACCPPI was created to fill in such loopholes. It has been recommended by CCPI reviewers that there is need for more robust indexes based on empirical scores or weighting systems. It is within this context that the African Climate Change Policy Performance Index (ACCPPI) was developed. ACCPPI uses four climate policy indicators (greenhouse emission score-GHGS, percent of renewable energy score-RES, climate policy score-CPS and corruption perception score-CRPS) that are represented in an index rated on 100% based on a specific rating scale and thus provides a baseline evaluation of the state of climate change policy performance across Africa (Fig. 2). Another index that is similar to the current is the readiness index (ClimAdaptCap Index) for climate change adaptation in Africa that incorporates a climate score (temperature and precipitation) and an adaptive capacity score (literacy and poverty rates) into a single index (Epule et al., 2021a, Epule et al., 2021b, Epule et al., 2021c). The only other approach that comes close to this current work is the Environmental Protection Index (EPI) developed by Hsu and Zomer (2014). The EPI ranks 180 countries based on nine priority environmental issues in two broad objectives which include the protection of human health and maintaining ecosystem vitality. However, the ACCPPI is different in that it uses four key climate change policy performance indicators to evaluate the climate change policy performance of African countries and regions. The objective of the ACCPPI is to provide the first comprehensive assessment of climate change policy performance in Africa as well as move the policy debate in Africa from emotional and rhetorical arguments to more data driven and evidence-based actions that facilitates performance tracking and accountability. This tool will be the standard bearer for comparing and tracking country preferences in the context of climate change policy and will be updated every five years to introduce new data and track new developments and inform climate change policy progress across Africa.

Methods

- Data collection and analysis

- Greenhouse gas emission score (GHGS)

- Renewable energy score (RES)

- Climate policy score (CPS)

- Corruption perception score (CPS)

- African Climate Change Policy Performance Index (ACCPPI)

Results

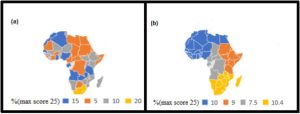

Greenhouse gas emission scores in Africa

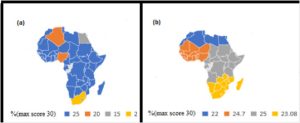

In terms of greenhouse gas emission scores, most countries in Africa scored 25% (Fig. 3a). This is because carbon dioxide emissions in Africa are among the lowest in the world. The countries with the score of 25% are represented in blue (Fig. 3a). According to the evaluation scale presented under the greenhouse emission score section (Table 1) of the methods of this work, a 25% score can be described as very low greenhouse gas emissions and consequently a higher greenhouse gas score. The second category of countries on the scale are Algeria and Nigeria which have a greenhouse gas emission score of 20% (low). Egypt records a score of 15% (medium) while South Africa records the lowest score of 2% (high) (Fig. 3a). Therefore, majority of the countries in Africa are within the very high score scale due to their relatively low carbon dioxide emissions when compared to other countries and regions of the world. The few exceptions are countries like South Africa and Egypt which record very low scores due to their higher carbon dioxide emissions.

Fig. 3. Greenhouse gas emission scores across (a) countries in Africa & (b) regions of Africa.

Regionally, the highest greenhouse gas scores are recorded in Middle Africa (25%), East Africa (25%) and West Africa which records 24.7% on a possible 30% (Fig. 3b). The scores in Middle and East Africa can be described as a reflection of relatively very low carbon dioxide emissions while those in West Africa fall within the relatively low carbon dioxide emissions scale. East, Middle and West Africa are some of the poorest, least industrialised, and consequently lowest emitters of greenhouse gases in Africa. On the other hand, the regions with the lowest greenhouse gas scores and consequently higher greenhouse gas emissions are Southern Africa (23.08%) and North Africa (22%) (Fig. 3b). These two regions are the wealthier regions of Africa with higher levels of industrialization and consequently higher greenhouse gas emissions. North Africa for example is host to countries like Algeria, and Egypt which have some of the highest greenhouse gas emissions in Africa while Southern Africa is host to South Africa which has the highest carbon dioxide emissions in Africa.

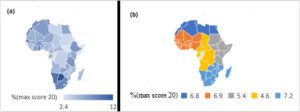

Renewable energy scores in Africa

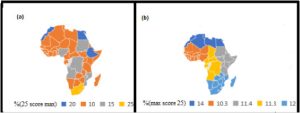

In terms of the percent of all energy that is renewable, South Africa which recorded the lowest greenhouse gas score in the previous section equally records the highest renewable energy score of 25% on a possible 25% (Fig. 4a). This can be described as a very high renewable energy score relative to other countries in Africa. Evidently, South Africa records more than 6000 MW of renewable energy investments. The second group of countries that have a score of 20% are Morocco, Egypt, and Ethiopia (Fig. 4a). The scores of the latter countries can be described as high. Significant here is the presence of Morocco which is among the groups of countries with the highest greenhouse gas emission score (i.e., lowest greenhouse gas emission in Africa) and now also recording a relatively high renewable energy score. These investments in renewable energies might be offsetting greenhouse gas emissions in some countries. Sudan, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola, and Mozambique have a medium score of 15%. The rest of the countries in Africa, have a renewable energy score of 10% which can be described as low (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4. Renewable energy scores across (a) countries in Africa & (b) regions of Africa.

In terms of regions, North Africa and Southern Africa record the highest renewable energy scores of 14% and 12% respectively (Fig. 4b). These regions are the wealthier regions of Africa with higher investments in renewable energy. Even though these regions are leading in this category in Africa, the fact that their scores are just within average of the 25% maximum score awarded for this category shows that much still must be done to valorized renewable energies in Africa. The other regions of Africa perform as follows, East Africa (11.4%), Middle Africa (11.3%) and West Africa (10.3%) relatively low scores with West Africa recording the lowest renewable energy scores (Fig. 4b).

Climate policy scores in Africa

In the context of climate policy, South Africa leads with a score of 20% on a possible 25% (Fig. 5a). This score is associated to the presence of a more open public sector policy and thus a more rigorous climate policy environment. The country is aware of its relatively higher carbon dioxide emissions and has consequently put in place policies to combat the problem. Despite these efforts, the countries with very high GHG emissions might not leverage this with the best climate performance in Africa. The second category of countries have a climate policy score of 15%. These are scaled at fair and include Morocco, Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, Tanzania, Zambia, and Angola (Fig. 5a). The rest of the countries in Africa which constitute a majority record scores of 10% and 5% respectively (Fig. 5a). These can be scaled as poor and very poor respectively. These results show that much of Africa is vulnerable to climate change impacts due to poor policy performance.

Fig. 5. Climate policy scores across (a) countries in Africa & (b) regions of Africa.

The regional results confirm the assertion that climate policy in Africa needs to be enhanced. With the highest potential score set at 25% for this category, the best score stands at 10.4% recorded in Southern Africa (Fig. 5b). This is followed by North and West Africa with scores of 10% (Fig. 5b). While the wealthier and more developed part of Africa have the highest climate policy scores, the lowest scores are recorded in the poorer and least developed parts of Africa such as East and Middle Africa of 9% and 7.5% respectively (Fig. 5 b).

Corruption perception scores in Africa

In terms of the corruption perception score (CPS), most of the countries record very low scores relative to the maximum score of 20%. Botswana records the highest CPS of 12%, Cape Verde records the second highest of 11.6%, Rwanda 10.8%, Mauritius 10.6%, Namibia 10.2%, and Senegal 9% (Fig. 6a). The latter scores can be described as medium as per the scale in the methods section. The rest of the countries either have a low or very low score depicting increasing levels of corruption. South Africa records a score of 8.8%, Morocco records a score of 8% and Egypt records 6.6%, all within the low score range (Fig. 6a). The higher scores depict relatively lower levels of corruption and consequently relatively higher public sector climate change policy performance.

Fig. 6. Corruption perception scores across (a) countries in Africa & (b) regions of Africa.

Regionally, Southern Africa records the highest score of 7.2% followed by West Africa (6.9%) and North Africa (6.8%) (Fig. 6b). These results though relatively low when compared to the maximum threshold of 20% for this category still depict that in relative terms these regions have relatively lower corruption levels. The lowest scores are in Middle Africa (4.6%) and East Africa (5.4%) (Fig. 6b).

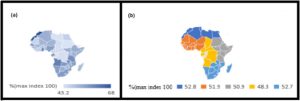

African Climate Change Policy Performance Index (ACCPPI)

The country with the highest ACCPPI is Morocco with a score of 68% (Fig. 7 a). Morocco’s climate change policy performance is consistent across the four scores that make up this index. This score can be described as medium or fair. Other countries that perform well are Cape Verde (61.6%), Angola (60.4%), Senegal (59%), Ghana (58.6%), Tanzania (57.6%), and Zambia (56.6%) (Fig. 7a). South Africa also records a score of 55.8% and together with countries like Nigeria falls within the medium or fair performance scale (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 7. African climate change policy performance indexes across (a) countries in Africa & (b) regions of Africa.

Regionally, North Africa records the highest ACCPPI of 52.8% followed by Southern Africa (52.7%). These regions have been consistent through out with respect to their relatively higher greenhouse gas scores, renewable energy scores, better climate policy and lower rates of corruption. The other regions such as West Africa record 51.9%, East Africa records 50.9% and the lowest score is recorded in Middle Africa (48.3%) (Fig. 7b). Also, the lower indexes are also consistent with lower renewable energies, poorer climate policy environment, and more corruption in the public sector. The only exceptions to this are in the context of greenhouse gas emissions where they have higher scores due to lower emissions, and lower levels of industrialization.

Discussion

One of the important findings from this work is that Morocco has the highest greenhouse gas emission and renewable energy scores in Africa and consequently the highest ACCPPI. Invariably, Morocco is standing out in Africa as a leader in greenhouse gas emissions reduction, renewable energies, and environmental protection in general. Morocco is one country that is making a lot of efforts in Africa and around the world to enhance climate change policy. Morocco’s leadership in these domains in Africa and globally is reflected in its environmental stewardship around the world and numerous projects that aim at curbing greenhouse gases as well as enhancing climate change policies. Morocco’s actions are already making news at the international, regional, and national scene as reflected in its 4th rank in the 2021 climate change performance index (CCPI) (German Watch, 2021). Under the CCPI, Morocco stands out at 67.59% among top climate change performers in the world behind Sweden 74.42%, United Kingdon 69.66% and Denmark 67.59% (German Watch, 2021). However, these should be handled with caution as these are not comparisons between the ACCPPI and the CCPI because the two approaches are used at different scales and are parametrized differently. ACCPPI is mainly a relational index that compares countries and regions of Africa in terms of climate change policy performance. Unfortunately, the CCPI only coveres four countries in Africa (Morocco, Egypt, South Africa, and Algeria), one of the reasons why this current study is carried out. The results of the ACCPPI are reliable; this is seen as the ACCPPI ranks Morocco at 68% while the other index (CCPI) ranks the latter at 67.59%.

In Morocco, the Mohammed VI Foundation for Environmental Protection is an example of an organizations that is leading ‘‘state of the art’’ projects with climate change policy implications. The foundation handles among others environmental stewardships in Morocco as well as internationally. It was launched by Her Royal Princess Lalla Hasnaa on April 23, 2009. The initiative is made of a program called ‘‘Air Climate’’ ‘‘Air Climat’’ which involves a voluntary carbon compensation program aimed at fighting climate warming by encouraging public and private enterprises to reduce carbon emissions linked to their activities or pay compensation for emissions under a polluter pay policy. The funds generated from this project have been used to: 1. Plant trees and Date Palms to sequester carbon, 2. Install solar panels in some rural schools/renewable energies, 3. Sensitize the population on the need to curbs Morocco’s environmental and energy footprints, 4. Handling waste management projects, 5. Sustainable transportation (Morocco CSAIP (2018); Foundation Mohammed VI for Environmental Protection, 2020; Schilling et al., 2020).

Furthermore, this work has found that South Africa has the highest greenhouse gas emissions in Africa as well as the highest renewable energy investments (Khan et al., 2014; Borges et al., 2015). Even though Africa accounts for only about 23-percent of the global carbon dioxide emissions, in Africa, South Africa leads the charts with over 133,562 K tons of carbon dioxide emissions. The second country in order of magnitude is Egypt with over 55, 057 K tons while other countries such as Algeria and Nigeria score 39, 651 K tons and 26, 256 K tons respectively (World Population Review, 2021). On the other hand, South Africa has the highest renewable energy potential in Africa of about 6065 MW followed by Egypt with about 4813 MW (World Population Review, 2021). The high rate of greenhouse gas emissions in South Africa are linked to the country’s leading investments in industrialization and agriculture (Khan et al., 2014; Borges et al., 2015). In the context of renewable energy, Africa has a huge potential envisaged at about 310 GW by 2030 but in the context of performance, these have not been harnessed yet because in many countries harnessing renewable energies requires investments in solar panels, hydro power plants and wind turbines (African Development BankAfDB, 2018). Therefore, much of the current investments in renewable energies are consistent with the richer parts of Africa which are capable of spending and investing on renewable energies, corruption reduction, and in climate policies. This is the case of regions like North Africa and Southern Africa which have higher GDPs per capita and concretely have more renewable energy projects in Africa (Bugaje, 2006).

In terms of climate policy, South Africa and Morocco lead the charts in Africa. These results are based on robust climate policies in these countries. For example, South Africa has enacted the following policies to grapple with climate change. In 2019 the Biofuels Regulatory Framework to implement biofuels in the transportation sector was implemented, the AfD Green Fund on energy efficiency and renewable energies was enacted, the low Emissions Development (LED) strategy 2050 was put in place, the Integrated Rescue Plan for electricity, heat, and coal as well as renewable energies and gas was enacted, the Carbon Tax for buildings, industry, agriculture, and forestry was implemented. In 2018 South Africa enacted the Green Transport Strategy and the Climate Change Bill. In Morocco, some of the climate policies include: the 2030 National Climate Plan of 2019, and the Exemplary Administration Pact. In 2018, decree number 2.17655 creating the Strategic Committee on Sustainable Development was created. In 2017 the National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2030 was put in place (New Climate Institute, 2021). In 2016, Morocco created the Nationally Determined Contribution that takes care of aspects related to energy efficiency and renewable resources. In 2014, the National Climate policy and the Framework law number 99–12 on the National Charter for Environment and Sustainable Development were enacted (New Climate Institute, 2021). Despite the proliferation of these ‘‘state of the arts’’ policies in South Africa and Morocco, it is worth mentioning that most countries in Africa score rates of very poor when it comes to concrete climate policies that are already being implemented. This partly accounts for the high level of vulnerability to the effects of climate change. This is the same observation for the regions like Middle, and East Africa that score poorly on the evaluation scale (Toulmin, 2009).

In terms of the corruption perception score, Africa generally has low scores due mainly to rife rates of public sector corruption, nepotism, and bureaucracy. The country that performs best in Africa is Botswana. On the other hand, there is increasing evidence that when there is corruption in the public sector, programs aimed at combating climate change are not easily implemented. The contribution of corruption in African climate change policy performance can mainly be evaluated in the context of the misallocation of resources which trigger detrimental effects on ecological efficiency. Corruption affects the proliferation of green economies in Africa (Biasutti and Giannini, 2006; Collier et al., 2008). Despite the huge potential and prospects of African countries to explore natural resources, most of these countries have not been able to explore the positive effects of good practices and policies. It further intensifies resource allocation and thereby lessening ecological efficiency (Ganda, 2020).

According to ACCPPI North and Southern Africa are the best performers in terms of climate change in Africa while countries like Morocco, Cape Verde, Angola, Ghana, and Senegal lead in the context of countries. An interesting observation is that a country like Botswana that has the highest CPS which depicts the lowest levels of corruption in Africa among the countries included does not appear among the top performers. This observation is important because the climate performance of any given country is complex and cannot be driven only by a single score. In evaluating climate policy performance, it is important to evaluate performance in key scores or variables. In the case of this work, we focus on variables that are perhaps some of the most important determinants of climate change around the world. Much of the debate on climate change policy around the world is focusing on greenhouse gas reductions, investments in renewable energies, favorable climate policy environment and reduced corruption (Ford and King, 2015). The outcome is often a function of all the variables acting together rather than just one. Like in South Africa, it is however possible that due to the very high intensity of greenhouse gas emissions, efforts in other sectors such as renewable energies are insufficient to turn the tides without sustained efforts. The result that the highest ACCPPI is obtained in North and Southern Africa is consistent with the findings from a new readiness index for climate change policy in Africa. The readiness index shows that due to lower poverty and higher literacy rates, North Africa and Southern Africa are the regions of Africa that are much more ready or prepared for climate change policy (Epule et al., 2021a, b, c).

Due to the findings from this study, it is now possible to evaluate the state of climate change policy performance in Africa. Prior to this work, the CCPI of German Watch only covered other regions of the world with only Morocco, Egypt, Algeria, and South Africa included (Burck et al., 2019; German Watch, 2021). This current work therefore builds on this previous index and creates an index that goes beyond greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energies, climate policies and integrates corruption. Despite the differences between this current index and the previous work, this current index is complementary to CCPI.

This current index was developed mainly to evaluate and assess climate change policy performance in Africa. A major advantage that it has is that it can be adjusted to the realities of other regions of the world. Furthermore, this work is enhanced by its ability to reflect key governance indicators such as climate policy and corruption that are pertinent in performance assessments. In fact, this index is capable of simulating performance based on any climatic and governance variables of interest under a given condition. The ability of the index to simulate both climatic and governance related variables brings the results very close to reality as often climate performance goes beyond physical climate actions such as planting of trees to include suitable policy environment to enhance success (Simelton et al., 2009; Epule et al., 2021a, b, c; Epule, 2021). In addition, the new index integrates measures for corruption, avoids co-linearity that exist between renewable energies and energy use and uses the scoring or weighting approach to quantify the indicators. This new index will play a major role in climate policy mapping in Africa and in other parts of the world. This is evident as it provides an opportunity for various stakeholders to have discussions around the different options that can be used to enhance climate change policy based on the areas where emphasis must be placed. This index has shown that climatic stressors are important but building resilience will not only be based on the magnitude of these stressors but most importantly on the degree of readiness which impacts climate change policy performance (Simelton et al., 2009). Therefore, identifying key climate change policy performance indicators across different countries and simulating them using this approach or developing others is key for the future of climate change performance monitoring (Biasutti and Giannini, 2006; Collier et al., 2008). It is also important to observe that there are other potential indicators that can be used to assess and measure climate change policy performance in Africa. Some of these include: the risk a country faces, the basis of the economy, poverty, literacy, inequality, war and conflicts, and equity linked to sustainability. However, most of these indicators are difficult to measure due to the absence of adequate proxies. In addition to this data availability limitation, it is often difficult to include all these indicators in one index. As such, this work based the choice of indicators on those that are the most relevant in assessing and measuring climate change policy performance in Africa. As concerns poverty and literacy, there is already an index that assess and measures readiness for climate change adaptation in Africa (Epule et al., 2021a). The latter is based on two key scores which are climate and adaptive capacity. The climate score incorporates temperature and precipitation, while the adaptive capacity score incorporates poverty and literacy rates. The difference between the latter and the ACCPPI is that the ACCPPI measures performance in the context of what has already been put in place while the readiness index focuses on preparedness for climate change adaptation through climate and adaptive capacity.

It is important for the nexus of actions to help enhance climate change policy performance in Africa to tap from an interplay of the co-benefits and synergies of mitigation and adaptations in Africa (Sharifi, 2021). This is important because the ACCPPI integrates both mitigation and adaptation to climate change. For example, the greenhouse gas and renewable energies scores are more within the context of mitigation as they enhance reductions in greenhouse gases. On the other hand, the climate policy and corruption scores of the ACCPPI underscore policies that can be of help in enhancing both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Invariably, policies towards climate change adaptation plans do enhance resilience. There is a consensus that integrating mitigation and adaptation is necessary in addressing climate change impacts and therefore a better understanding of their interactions is required to sufficiently maximise their potentials (Sharifi, 2021). The co-benefits of mitigation and adaptation are often related to sectors such as greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energies, energy policy, climate policy and corruption (Sharifi, 2021). This approach is important because it offers opportunities to tap from the co-benefits and synergies of greenhouse gas emissions reduction and climate change adaptation actions through climate policies which all aim at the establishment of resilience (Sharifi, 2021). It has been noted that, the approach of combining mitigation and adaptation into climate policy is not an often-used approach as depicted by a lack of research on this in the global south (Sharifi, 2021). Therefore, climate change policies that provide co-benefits and synergies need to adopt empirical approaches to enhance our understanding of synergies and co-benefits of climate change mitigation and adaptation (Sharifi, 2021).

Conclusion

Countries and regions with higher greenhouse emission reduction policies, more renewable energy investments, efficient climate policy and reduced corruption are more likely to have better climate policy performance. In the context of Africa, North Africa and Southern Africa record the highest ACCPPI. Though this study focuses only on the four most important scores, it is important to argue that there are likely several other proxies of climate change policy performance. Despite this, through ground truthing, this study observes that the four scores/variables used here are transversal and cut across the other potential variables. The ACCPPI introduced in this study is complementary to the CCPI which has been used to assess climate change policy performance by the German Watch (2021). However, the difference between this current approach and the German Watch version is that it dwells on only four African countries and does not integrate corruption perceptions. However, the main weakness of this work is the difficulty associated with the measurement of climate change policy performance being that a ubiquitous number of potential indicators might exist. Therefore, selecting indicators that are representative is very important. Secondly, the data landscape across Africa is highly limiting and this explains why German Watch was unable to extend its approach beyond four African countries. This current index is based on a score-based approach which assigns scores for each of the four indicators. The use of scores has been criticized as a weak approach to assigning weights or in evaluating performance because they are not based on empirical computations. However, the fact that the scores are based on the intensity of specific indicators and aligned with percentages makes the approach to be rational. While this work has found that countries like Morocco are performing well in all categories, countries like South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, and Nigeria do not perform very well when it comes to greenhouse gas emissions. South Africa for example does well in all the other scores except for greenhouse gases which brings down its general performance. For this group of countries, policy recommendations aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions are highly favorable. This can be achieved through investments in renewable energies as is the case in South Africa which has the highest renewable energy scores. This high renewable energy score is already off setting the high greenhouse gas scores. Another important policy recommendation will therefore be for this category of countries to resort to increase reforestation especially with the recent outcomes of COP26 and within the framework of the intention to curb deforestation by 2030 and a promise by the European Union to invest 2.5 billion euros in fighting deforestation in the Congo Basin. Most countries in Africa are low greenhouse gas emitters and should therefore focus on renewable energies, climate policy and in combating public sector corruption. This will create a suitable atmosphere for sustainable economic development and investments in clean energy solutions and policy. Regionally, North and Southern Africa have the highest ACCPPI while the rest of Africa’s performance is on the low scale range. The low performing regions need to enhance their investments in renewable energies, climate policy and corruption reduction while the high performing regions should focus on reducing their greenhouse gas emissions. In the future, it will be necessary to test this index at sub-national scales in individual African countries to see how climate change policy performance can be simulated at much finer scales. It could be vital to introduce other proxies of climate change policy performance and evaluate and compare how the index performs under different circumstances. Finally, studies based on projections of likely future trends will go a long way to enhance monitoring policy.

Source : https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2665972721000647#abs0015

Author

-

Prof. Terence Epule Epule is Professor of Agroclimate and Adaptation Sciences at Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue (UQAT). Before this, he was Assistant Professor of Climate Change Adaptation at the International Water Research Institute (IWRI). His research is at the interface of climate, agriculture, and adaptations. He has published more than sixty-one peer-reviewed journal articles, two books, and seven book chapters.