Synopsis: Bengaluru faces a severe water crisis, with demand far exceeding sustainable supply. The new Greater Bengaluru Authority aims to unify urban planning, while citizen group paani Earth pushes for watershed-based planning, better data access, and genuine lake restoration. Their “Waterscapes of Bangalore” exhibit urges public action, stressing that Bengaluru’s survival hinges on respecting its natural water systems.

With a population now touching 14.4 million and growing at 2.76 percent annually, the pressure on Bengaluru’s water system has reached alarming levels.

According to WELL Labs data, every day, the city demands 2,632 MLD (Megaliters per Day) of freshwater—but only a little over half of that comes from the Kaveri River. The rest? It’s mostly groundwater, extracted at an unsustainable rate—1,372 MLD, far exceeding the 148 MLD that nature can replenish.

This is where the Greater Bengaluru Authority (GBA) comes in—a newly formed body tasked with unifying the city’s planning efforts across urban and peri-urban areas. For the citizen run NGO paani Earth and other citizens, the GBA represents a rare chance to rethink how Bengaluru handles its most precious resource.

Bridging the data gap

“Most people don’t even have access to the data they need, to understand what’s happening,” says Khushbu Birawat, a full-time researcher at paani Earth, adding, “Even though we have the Right to Information Act, much of the environmental data is hidden or hard to find.”

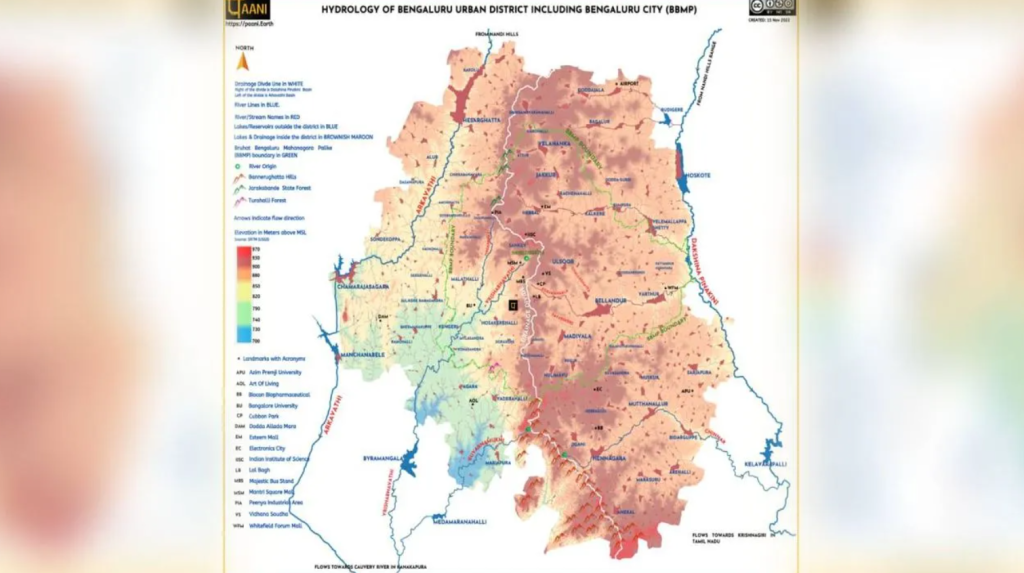

To bridge this gap, paani Earth has taken it upon itself to document river systems like the Kaveri, Vrishabhavathi and Arkavati, publishing open-access maps and launching pilot projects like Rivers for Life—a grassroots experiment in river rejuvenation inspired by successful models like the Kham River restoration in Aurangabad.

City planning

Khushbu also points to the city’s cycle of droughts and floods—a pattern that’s been repeating since 2013. The culprit? Decades of urbanisation and concretisation, which have blocked the natural flow and absorption of water. She argues that the only way out is to plan around watersheds and valleys, not outdated ward boundaries.

“Water doesn’t follow man-made lines,” she says. “It flows through nature’s pathways—valleys and basins. Bengaluru is built on three major valley systems, and each of them feeds into larger basins. If we don’t respect that, our water problems will only get worse.”

But there’s more standing in the way than poor planning. Rainwater harvesting laws are barely enforced. Lakes are often neglected, or worse, given a cosmetic facelift with walking tracks and gyms while their ecosystems die silently beneath the surface.

“What we call lake rejuvenation is often just greenwashing,” Khushbu says. “We need real restoration—where lakes function as ecosystems, not just pretty parks.”

Role of citizens

The role of citizens is crucial in all of this. While Bengaluru has its share of passionate resident groups, widespread apathy still haunts efforts to protect its natural spaces. “The government only moves when the people demand it,” Khusbu says. “We need more people to care, to ask the right questions, to hold leaders accountable.”

To spark that public engagement, paani Earth is currently hosting Waterscapes of Bangalore, an interactive exhibition at the Vishveshwaraya Technological Museum, running until 15 August. Through maps, stories, and immersive displays, it hopes to remind Bengalureans of the rivers they’ve forgotten—and the ones that could still be saved.

As the GBA finds its footing, Khushbu and others like her believe the time for change is now. “By Independence Day, I hope we can raise enough awareness and inspire conversations and actions so that our rivers can flow freely again and become unpolluted soon.”

Because Bengaluru’s future depends not just on how it builds—but on where and how water flows.

Source link : View Article

Author

-

Sanjana Shashidhar is a student of Psychology and Communicative English with a passion for the performing arts. She is now exploring her growing interest in journalism.