India must invest more in weather monitoring systems to safeguard and leverage its maritime commerce

India reported a dramatic increase in its coastline measurement – from 7,518 km to 11,510 km – thanks to comprehensive surveys utilising advanced geospatial technology. This significant expansion reinforces India’s status as a maritime powerhouse, strategically positioned along the world’s most vital shipping corridors with its network of 12 major ports and over 200 minor harbours.

India’s maritime significance is underscored by its oversight of 80% of global maritime oil trade, while its ports manage an impressive 95% of the nation’s trade volume and 68% by value. However, this vital economic artery remains highly vulnerable to an often-overlooked threat: extreme weather events. Such events over the past few years have severely impacted global shipping operations. The 2023 drought continues to affect Panama Canal’s capacity, while severe weather caused 1,629 shipping containers to be lost annually during 2020-2021. The 2015 sinking of cargo ship El-Faro which claimed 33 lives highlighted the dangers of relying on delayed weather information.

With vessels often carrying cargo worth millions of dollars, these weather-related disruptions remind of the susceptibility of maritime trade and the need for preemptive planning. The United States pioneered systematic maritime weather monitoring with NOAA’s Physical Oceanographic Real-Time System (PORTS). Born out of tragic maritime accidents in the 1980s, including a collision between a Coast Guard vessel and an oil tanker that killed 23 people, PORTS provides near-instantaneous data on water levels, currents, salinity, and weather conditions crucial for safe navigation.

Japan’s Meteorological Agency operates extensive coastal radar systems and automated ocean observation ships, with integrated tsunami and storm surge sensors with real-time alerts. Australia utilises real-time ocean current forecasts for shipping route optimisation, achieving 3-5% fuel savings per voyage. The European Union’s Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service provides high-resolution maritime data across regional seas.

The Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services (INCOIS)’s Indian Ocean Forecasting System (INDOFOS) provides 5-7 day forecasts on various maritime parameters, including sea surface currents and temperatures, astronomical tides, wind conditions, and oil-spill trajectories to a wide range of stakeholders. The Indian Navy’s Information Fusion Centre-Indian Ocean Region (IFC-IOR) further cemented India’s strategic commitment to regional maritime safety and security.

INCOIS also has plans to install at least two buoys per coastal state and expand its fleet of ship-mounted automatic weather stations to 100 units. These initiatives can establish a high-wave alert service, enabling access to critical region-based information during cyclone events.

However, significant gaps remain. India has sparse sensor networks, especially at smaller ports, lacking real-time updates crucial for piloting and docking operations. Most notably, India remains heavily dependent on US-owned satellites like Aqua, Terra, and MODIS for certain oceanographic data.

Economic imperative

The growth trajectory of India’s maritime sector is remarkable, with trade volume expanding at a 5.2% compound annual rate between 2019 and 2024 – more than double the global pace of 2%. This exceptional performance, coupled with the government’s ambitious plans for sustaining cargo traffic growth between 3-6% annually, signals India’s emergence as a dominant maritime power.

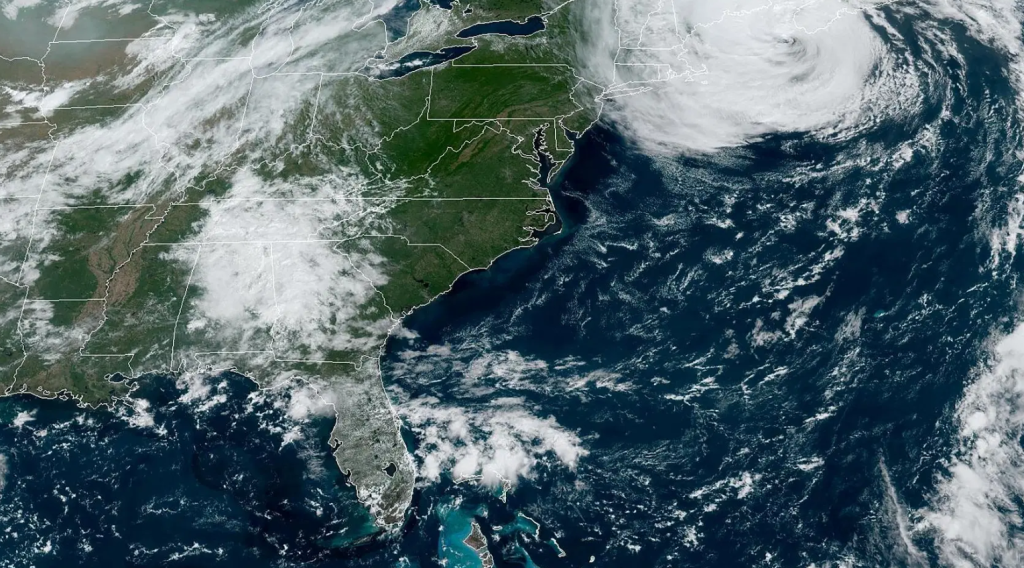

However, with the Indian Ocean warming faster than global averages – a trend expected to continue this century, very severe cyclonic storms in the region have increased by roughly one event per decade during post-monsoon seasons. These intensifying climate patterns will significantly impact India’s growing ocean-based economy in the coming years.

Global weather services lack the granular, real-time data for local maritime operations. Indigenous systems provide crucial localised updates tailored to specific coastal characteristics. During extreme weather events, even minute communication delays can be catastrophic. Regional weather patterns and coastal topography require specialised calibration algorithms rarely optimised by foreign systems, leading to forecast errors in unique meteorological zones like monsoon-affected coastlines. Foreign satellites prioritise data collection for their operating nations’ interests, creating coverage gaps in critical areas for other countries.

Hence, India needs to recognise that advanced weather monitoring is not merely an environmental or research endeavour but a primary economic security investment. India must invest more in indigenous satellite capabilities, expand coastal sensor networks, and develop port-specific monitoring systems integrated with operational decision-making. The country needs to move beyond foreign satellite dependency and create weather intelligence tailored to its unique geography.

By treating weather monitoring as critical infrastructure, India can protect its maritime trade from volatile weather, enhance efficiency, and secure its economic future in an uncertain climate era.

(The writer is a research analyst at the Takshashila Institution)

Source link : Read article

Author

-

Swathi Kalyani is a Research Analyst with the Geospatial Programme at the Takshashila Institution, where she focuses on applying the principles of mapping and spatial analysis to understand real-world problems. She contributes to public discourse as a co-host on the "All Things Policy" podcast, discussing topics like coastline delineation, the Indus Waters Treaty and more.