Summary

As the dust settles on the UK elections, our UK lead Dr Neil Grant looks at the climate challenges ahead for Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and his Energy Secretary Ed Miliband.

The biggest challenge – and indeed opportunity – for the new UK government, is to take the lead on 1.5ºC-aligned climate action, both at home and abroad.

Policies stalled – and then started going backwards under the previous Conservative government, demonstrating a serious lack of commitment to reducing emissions.

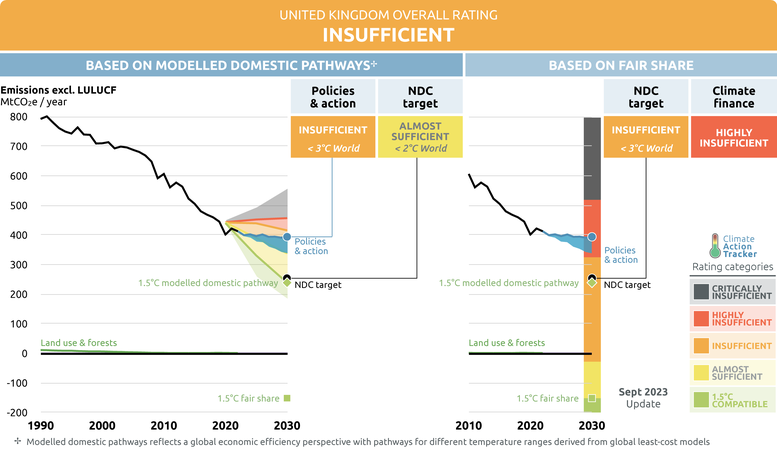

In our 2023 UK analysis, we found that less than 20% of the greenhouse gas emission cuts needed to meet the UK’s current 2030 target are covered by credible policies, amid continued delays to policy design and implementation, and an active weakening of key existing policies. We will update this analysis later this year once the new government has begun work.

What can Keir Starmer’s new government do to reverse this weakening of climate action?

Labour had set out a range of key climate policies in its election manifesto, that – if implemented – would send a positive signal that the UK can – and is – acting to address the climate crisis.

The first is to achieve clean power by 2030: this would align emissions with the CAT benchmarks for the UK of 96-98% clean power by 2030. It will take a herculean effort, but is absolutely achievable and likely lead to lower electricity bills across the UK. It would also send a strong message to the international community: that a fossil-free power sector is achievable. Achieving this target could accelerate the race to clean power in other countries.

However, emissions from the power sector only made up 14% of UK emissions in 2023, while transport and buildings represented 28% and 20% respectively. Action is urgently needed in these sectors as well.

Labour aims to double investment into energy efficiency in buildings: this is crucial, but the government needs to ensure the funds go to those who need it most, to those experiencing fuel poverty. This is an essential part of a just transition framework for the country.

Prime Minister Starmer would be wise to reconsider his promise to revoke the ban on new gas boilers. Credible long-term bans on fossil fuel technologies can – and have been – very useful in setting out a clear direction of travel for a sector, and should not be scrapped.

On transport, the reinstatement of 2030 as the end date for sales of new petrol and diesel cars would be welcome. But it remains unclear as to how the government will achieve a zero-emissions transport sector, as it still lacks detailed plans for public transport, a clear commitment to halt airport expansion and more.

One major challenge in the transport sector is aviation. The previous administration’s’ “Jet Zero” aviation emissions strategy will see continued growth in the aviation sector, with airport expansion planned across the country, despite clear recommendations from the Climate Change Committee to the contrary.

This policy is heavily reliant on offsets to compensate for fossil fuel emissions, and on the (currently very small and expensive) supply of sustainable aviation fuels. To allow aviation emissions to continue increasing by the projected 70% between 2021 and 2050 and just offset them is a deeply flawed strategy. There has been no indication yet from either Starmer or Miliband that they plan to deviate from this policy. [See our UK country analysis of the aviation sector for more details].

Another key Labour policy is to stop new oil and gas licenses in the North Sea. This is a good first step which aligns with the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions (NZE) scenario that states there can be no new investment in fossil fuel exploration or production if we are to limit warming to 1.5ºC. However, Labour can and should go further, committing to end approvals of any new fields which have already received exploration licenses but don’t yet have the field development consent that is required for new production. Labour could also come out clearly against the enormous Rosebank oil field, whose approval by the previous government is currently being contested in the courts. This is a carbon bomb that could, and should, be avoided.

International focus

While domestic action will be key to putting the UK at the front of climate action, action in the international climate arena will also be essential. There is no clear indication to date on how the new government will proceed. In the past, the UK government has taken a lead in driving high ambition in climate negotiations. Will Starmer be able to bring this back?

With increasing international headwinds on climate action, a resumption of the UK government’s historic role in pushing high ambition internationally is both an urgent need and an historic opportunity for the new UK government.

There are two key issues here – climate action (ambition) and finance. The new government is taking power at a critical moment, where countries are being asked to provide updated and 1.5˚C-aligned climate plans (or NDCs) under their UNFCCC obligations for 2030 and 2035.

The UK’s current 2030 target is close to aligning with 1.5ºC, but could and should be strengthened further. An ambitious 2035 target is also needed. Our latest briefing on what a good NDC looks like could be useful reading for Starmer and his team.

The issue of climate finance to developing countries is absolutely critical to any forward movement in the global climate game, and the UK needs to make much bigger commitments here, and reverse the previous administration’s climate finance cuts, which have severely eroded the UK’s global reputation. In our last analysis of the UK’s climate action, we gave it a “Critically insufficient” rating. This needs major improvement, and fast.

Sectoral strategies needed

We have other recommendations for the new UK government, as we set out for all countries. These include:

- Publish overarching sectoral strategies to drive system-wide decarbonisation. There are no sectoral plans for power, agricultural and land-use sectors, despite repeated calls for their development.

- Promote industrial electrification which, unlike hydrogen and Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), has no business models to support it.

Address the overreliance on technological innovation to deliver emission reductions, particularly in aviation and agriculture. Supporting and accelerating demand reduction strategies will be key to unlocking rapid emissions cuts

Source link : View Article

Author

-

Dr. Neil Grant is a Senior Climate and Energy Analyst at Climate Analytics. His work focuses on producing and assessing decarbonisation scenarios at both the global and national levels. He evaluates the actions required from individual countries to meet 1.5°C compatible targets and identifies opportunities to close the ambition gap and achieve the goals set by the Paris Agreement.