The venerable concept of the “Global South” has enjoyed a remarkable revival as a descriptor of postcolonial and developing country solidarity in world affairs. The term’s resurgence, however, has also engendered pushback, with many calling for a phaseout of the expression. Writing in the Financial Times, columnist Alan Beattie calls the label “patronising, factually inaccurate, a contradiction in terms,” and “deeply unhelpful.” In Foreign Policy, Indian strategist C. Raja Mohan argues that the phrase “denies agency to individual countries by treating them as one bloc” with “fluid boundaries and vague criteria for inclusion.”

Some criticism of the term is superficial, based on a literal interpretation of the phrase as denoting countries below the equator, with critics noting, for example, that India falls above that line, while wealthier Australia and New Zealand fall below it. Others carry more weight, like the charge that the Global South is often used as a sloppy, catchall synonym for “developing countries” or the “Third World.” Further, the analytical purchase of the phrase is limited, as one of us has pointed out, because the concept purports to capture an array of nations that differ markedly in their governing systems, economic circumstances, strategic alignments, and cultural identities.

Such critiques should not, however, obscure the term’s continued political salience and symbolic potency more than half a century after the phrase was coined. Across the decades, the concept of the Global South has resonated with governments and citizens of lower- and middle-income countries because it is an expression of perceived exclusion from—and rejection of—enduring hierarchies in world politics. Using the Global South and related terms became advantageous, including for members of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) that sought to avoid choosing sides in the Cold War, precisely because these terms unified a diverse set of nations behind a common program: to amplify the voice and agency of countries in historically subordinate positions by pooling their economic and political strength to force a rebalancing of global power.

Historical analysis thus illustrates that, rather than using the Global South to mean a rigid grouping of nations, it is more helpful to understand it as an organizing principle to guide a reimagining of a more just international economy and world order. Appreciating the continuity between twentieth-century anticolonial movements and contemporary political issues clarifies the perspectives and choices of many in the Global South for policymakers in the United States and the rest of the so-called Global North. To some in the world, the central divide in the international sphere remains that between the dominant North and the aggrieved South, rather than that between democracies and autocracies.

The Global South and Theories of Colonialism and Imperialism

American political activist Carl Oglesby is thought to have coined the term Global South in 1969 in Commonweal to denote a set of countries beset by the “dominance” of the Global North through political and economic exploitation.1 Oglesby’s work built on an earlier twentieth-century intellectual tradition, often radical and left-wing in nature, that portrayed the global order as created by a wealthy and politically powerful subset of nations. Such nations, from this perspective, built their positioning through economic exploitation of the rest of the world, particularly through imperial rule, and subsequently continued to maintain this unequal positioning.

Numerous political theorists in the early twentieth century contributed to this tradition, including J. A. Hobson, Vladimir Lenin, Antonio Gramsci, and W. E. B. Du Bois. In his magnum opus Imperialism, the British socialist Hobson identified what he called the “taproot of imperialism”: the relentless search by capitalist oligarchs for market profits no longer available in their home countries. Building on Hobson’s thesis, Marxist theorists like Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg depicted imperialism as the highest stage of capitalism, one that created a global class division between countries that had accumulated capital and countries that they had exploited. In his 1926 essay “The Southern Question,” Gramsci applied the same analysis to his own country, arguing that capitalists from northern Italy had effectively colonized its south, creating an unequal relationship of dependency. (Indeed, some political theorists argue that the idea of the Global South is an extension of Gramsci’s analysis of Italy.) Meanwhile the African American intellectual Du Bois, writing in 1925, added a racial dimension to this argument, maintaining that European states used political coercion and economic compulsion to create a racialized global hierarchy that resulted in an international “color line.”

Later, anticolonial nationalists built on these ideas, arguing that the end of formal colonial rule was not enough to erase the hierarchies that empire had embedded in the world system. Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of an independent Ghana, maintained that decolonization had done nothing to alter the structural subordination of former colonies to former metropoles, much less to return stolen wealth and resources. Newly independent states remained vulnerable to political and economic coercion by wealthy states and former colonial powers. For African states to overcome this vulnerability, Nkrumah advocated pan-Africanism, including the pooling of economic resources and political might. One of Nkrumah’s contemporaries, the Martinican doctor Frantz Fanon, similarly argued in his 1961 book The Wretched of the Earth that the dehumanizing process of colonialism had created a world that naturalized the superiority of the colonizer and the inferiority of the colonized into an enduring “Manichaean” divide. In the eyes of such thinkers, the postcolonial era continued colonization by other means, resulting in an era of neocolonialism.

Finally, Oglesby’s writing built on (and referenced) dependency theory. This school of thought, pioneered in the 1950s and 1960s by economists Raúl Prebisch and Hans Singer, among others, attributed the lack of industrialization and the persistence of poverty in developing countries to the unequal structure of the world economy. According to this theory, countries on the “periphery” are locked in a state of dependency because they primarily export raw resources to wealthy countries of the global “core,” which then export value-added manufactured goods back to the periphery. Wealthy nations thus control the terms of trade, perpetuating this dependence. As Oglesby explained, poorer countries inevitably confront “higher import prices, lower export earnings,” and “rising debt, shrinking ability to finance the debt.” Dependency theory stood in contrast to modernization theory, which posited that all societies move through similar stages of development and that “underdeveloped” post-colonial states could “catch up” to developed countries if they pursued the right policies. According to dependency theory, undoing global poverty required substantially restructuring the global economy and reducing the power of core countries.

Organizing the Periphery: Political Action Toward a New Global Order

By 1969, these worldviews had inspired many governments of countries now considered part of the Global South to reshape the global order. This agenda had two main objectives, often pursued along separate diplomatic tracks: asserting geopolitical nonalignment and demanding a structural overhaul of the world economy. The main multilateral vehicles created to advance these goals, the NAM and the Group of 77 (G77), persist to this day.

The NAM emerged from the Asian-African Conference (or Bandung Conference) of 1955, a gathering of twenty-nine countries representing half the world’s population in Bandung, Indonesia, to facilitate anticolonial cooperation. Jointly organized by Burma (Myanmar), Ceylon (Sri Lanka), India, Indonesia, and Pakistan, the conference also included delegations from Afghanistan, Cambodia, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, the Gold Coast (Ghana), Iran, Iraq, Japan, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Nepal, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Türkiye, North Vietnam, South Vietnam and Yemen.

In his opening address, Indonesian president Sukarno described a world in which “colonialism is not yet dead” but had merely donned “modern dress, in the form of economic control, intellectual control, [and] actual physical control by a small but alien community within a nation.” The message was clear: the era of formal empire might be ending, but newly emancipated nations remained in subordinate positions.

The final communiqué of the Bandung Conference endorsed a posture of nonalignment as the only means for postcolonial nations to ensure independence and security in an unequal global order. The Bandung generation championed nonalignment, lest attachment to either the Western or Soviet bloc further expose them to foreign control or coercion. The communiqué asserted the right of all countries to self-determination, including “to choose their own political and economic systems.” Six years after Bandung, in 1961, the NAM held its First Summit Conference of Heads of State or Government in Belgrade, then a part of Yugoslavia. Beyond formally establishing the NAM, the assembled leaders declared the need to “transition from an old order based on domination to a new order based on cooperation between nations.” Nonalignment would be a tool to remake the global order in line with this vision.

In parallel with geopolitical nonalignment, the leaders of the incipient Global South sought to overhaul the global economic order. In 1964, representatives from 120 countries, as well as international organizations and civil society groups, convened in Geneva for the first gathering of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Prebisch served as UNCTAD’s founding secretary-general. There, a group of seventy-seven nonaligned nations issued the Joint Declaration of the Seventy-Seven Developing Countries, establishing what became known as the G77. Inspired by dependency theory, the G77 sought to address the economic needs of developing countries, primarily by promoting manufacturing capacity within poorer nations. Rather than exporting raw materials to industrialized nations, the G77 hoped to produce finished goods domestically and thus reduce their dependence on wealthy countries.

In effect, the architects of the NAM and the G77 were responding to the twin facets of an unequal and unjust international order that subordinated the Global South to the Global North. Nonalignment was a geopolitical strategy to protect national sovereignty and expand diplomatic room for maneuvering in a world of superpower competition. The G77’s economic advocacy and action aimed to compensate for and ultimately undo an inequitable world economy. Together, the NAM and the G77 offered useful multilateral platforms for countries of the Global South to build solidarity, overcome their individual powerlessness, and level a playing field tilted against them.

The Rise and Fall of the Global South

During the 1970s, many developing nations, unified by groupings like the NAM and the G77, coalesced around a set of proposals known as the New International Economic Order (NIEO). The NIEO emerged from the economic declaration of the 1973 NAM summit in Algiers, which expressed disillusionment that the wave of decolonization in the 1960s had brought little shared prosperity because of the unchanged structure of the global economy.

Building on the 1973 summit in Algiers, a preparatory committee of G77 countries, acting under the auspices of UNCTAD, drafted two resolutions: the Declaration for the Establishment of a New International Economic Order and a corresponding program of action. Adopted by the UN General Assembly without a vote on May 1, 1974, the NIEO declaration enumerated twenty principles. These included (among others) the sovereign equality of states, their right to political and economic self-determination, liberation from “alien and colonial domination or apartheid,” restitution for colonization, the right of developing countries to preferential economic treatment, and a “just and equitable relationship” between the prices of goods exported and imported by developing countries. The NIEO program also called for reforms to advance the industrialization of—and transfer of technology to—developing countries, to increase regulation of transnational corporations, to establish a Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States, and to reaffirm sovereign control over natural resources.

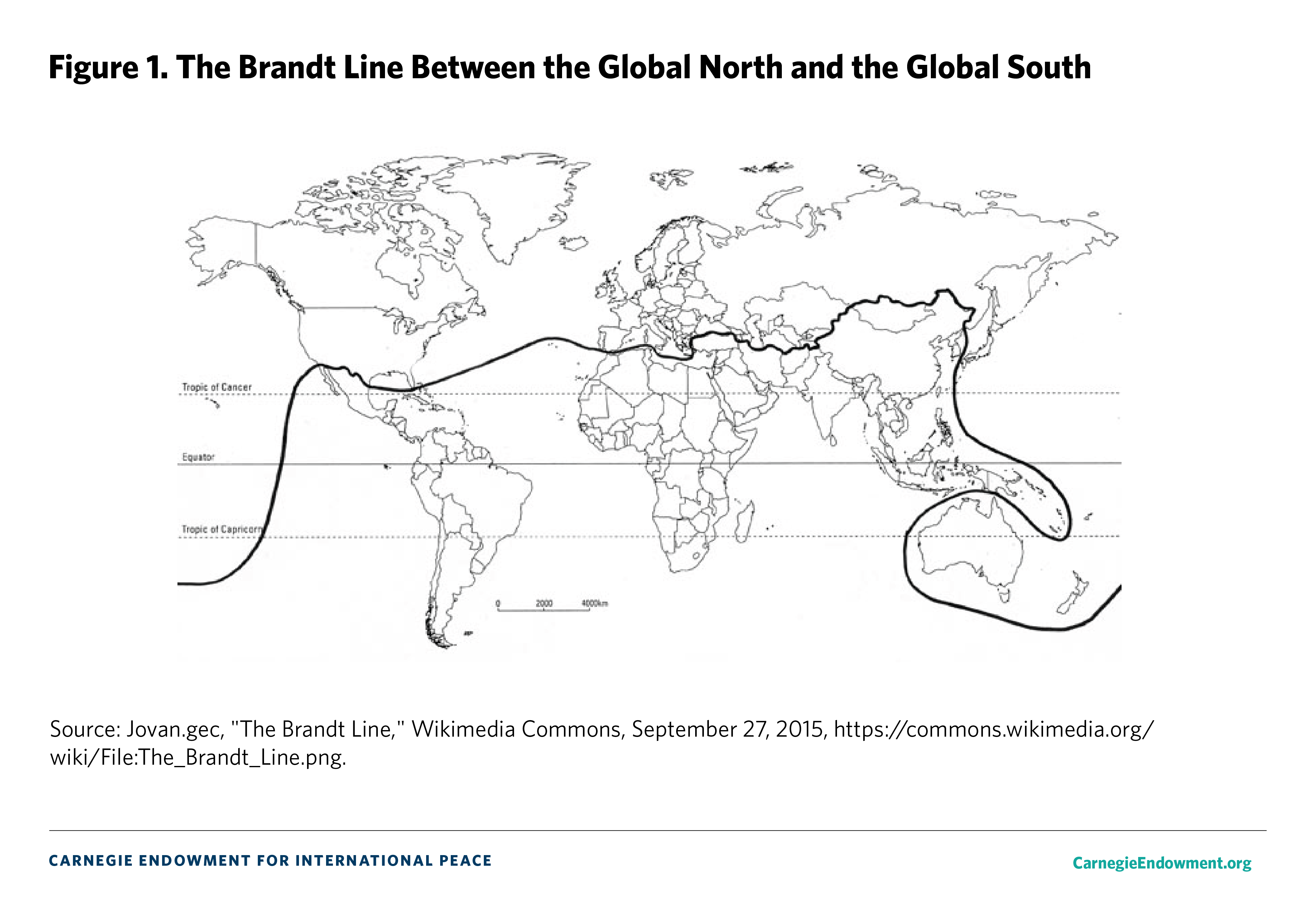

The NIEO’s principles and proposed reforms were echoed in a groundbreaking report, North-South: A Programme for Survival, released in 1980 by the Independent Commission on International Development Issues. Led by former West German chancellor Willy Brandt and comprising twenty-one prominent members from around the world and across disciplines, the commission had been established in 1977 by World Bank president Robert McNamara, who hoped to break the political impasse between the Global North and South on measures needed to support global economic development. The report, quickly christened the Brandt Report, featured a map on its cover, shown in figure 1, that became a commonly used shorthand to demarcate the countries belonging to the Global South.

Anticipating some contemporary critiques, the report acknowledged, “there are obvious objections to a simplified view of the world as being divided into two camps.” It also conceded that “the ‘South’ ranges from a booming half-industrial nation like Brazil to poor landlocked or island countries such as Chad or the Maldives.” Nevertheless, it insisted, “the nations of the South see themselves as sharing a common predicament. Their solidarity in global negotiations stems from the awareness of being dependent on the North, and unequal with it; and a great many of them are bound together by their colonial experience.” The commission therefore recognized that the countries of the Global South—despite their unique positionings—were united in political solidarity out of a shared belief that their individual struggles connected to the same core problem of global economic and political subordination.

The commission’s advocacy proved unpersuasive in the West, and the movement to enact the NIEO faltered. From the NIEO’s inception, the United States led the charge against it. The administrations of presidents Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, and especially Ronald Reagan depicted the NIEO as a radical, socialist-inspired scheme and proposed free market policies and domestic governance reforms as an alternative path to prosperity. The debt crisis of the 1980s lent a final blow, forcing many governments that had previously advocated the NIEO to adopt neoliberal policies, including to obtain access to much-needed liquidity from the International Monetary Fund. Rather than realizing structural reforms to the global economy consistent with the NIEO, the Global South was met with the structural adjustment programs of the Washington Consensus.

Explanations for the downfall of the NIEO differ in a way that mirrors the divergence of contemporary perspectives on the idea of the Global South. To those convinced that the NIEO floundered because the neoliberal, Western-led vision of global governance offered a more compelling vision than dependency theory and critiques of neocolonialism, the resurgence of the Global South is at best a naive revival of an outdated idea and at worst a cynical ploy to mask failures of domestic governance with unjustified international grievances. For proponents of the NIEO, and for those who continue to see inequity in the global system, the fall of the NIEO is emblematic of the injustice inherent to the structure of the global political economy, showcasing how the Global North is able to stymie the ambitions of the Global Majority.

The Global South Returns

In recent years, the idea that the global political and economic order divides the world into two unequal factions has returned to the global stage. In December 2022, the UN General Assembly once again adopted a resolution entitled “Towards a New International Economic Order,” calling for a revival of the NIEO of the 1970s. The vote split for and against the resolution mirrored the Brandt Line dividing the Global North and South almost exactly, with the United States, Canada, Japan, South Korea, Israel, New Zealand, Australia, and Europe voting against the resolution, while the rest of the world voted in favor, with the exception of an abstention from Türkiye.

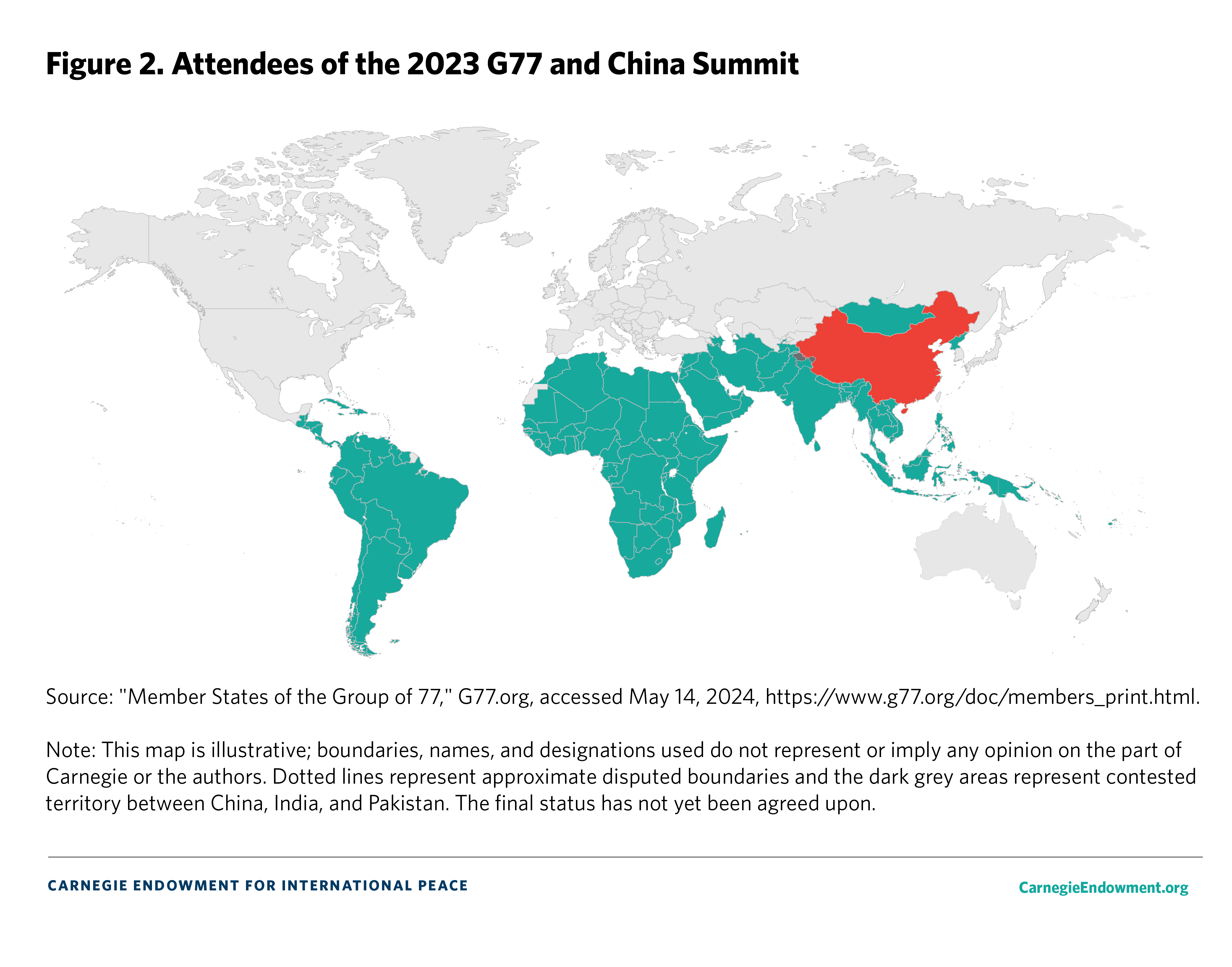

The rising popularity of the Global South term reflects renewed grievances against the global order and the need for those currently disempowered to band together to overhaul it. At the 2024 Munich Security Conference, President Nana Akufo-Addo of Ghana described an inherent instability to the global order produced by “a situation whereby the so-called Global South, where Africa features, is always at the wrong end of the stick in terms of its take-up of global assets.” At the G77 and China Summit in September 2023 (see figure 2), Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel echoed decades of NAM, G77, and NIEO rhetoric in declaring that “after all this time that the North has organized the world according to its interests, it is now up to the South to change the rules of the game.”

In September 2023, in a speech to the UN General Assembly, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil observed, “the richest 10% of the world’s population are responsible for almost half of all carbon released into the atmosphere,” yet “it is the vulnerable populations in the Global South who are most affected by the loss and damage caused by climate change.” Referring to the conflict in Gaza, President Gustavo Petro of Colombia has argued, “Germany

. . . France, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and above all, the United States of America . . . support dropping bombs on people because they are making a demonstration in front of the whole of humanity, that what happens to Palestine can happen to any of you if you dare to make changes without their permission.” The precise political causes the Global South pursues have shifted, but the core grievances remain the same.

Further, leaders of the Global South are displaying a renewed willingness and ability to buck the desires of the West. From Latin America to Africa, nonalignment has returned as a doctrine of foreign policy, preventing the West from building a global consensus around the war in Ukraine, among other issues. Consider the BRICS group, made up of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa until 2024, when it welcomed four new members (Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates) and was dubbed BRICS+. Although its efforts remain nascent, the BRICS grouping has sought to diminish U.S. dominance of the global financial system by diversifying away from the U.S. dollar and the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) payment system, while establishing new international financial institutions such as the New Development Bank. With its expanded membership, the grouping is positioning itself as a potential counterweight to the G7 and other Western forums. Countries of the Global South are also turning to international bodies in an effort to hold the Global North accountable, as evinced by the cases that South Africa and Nicaragua have brought to the International Court of Justice in connection with the Israel-Hamas war.

If this resurgence of the Global South reflects a desire for a new attempt at a more equal global order, an attempt that previously faltered during the 1980s, what has changed in the meantime? From 1990 to 2020, a key metric of wealth inequality (the global Gini coefficient) fell, indicating a reduction in economic inequality between countries. Countries like India, Indonesia, and Brazil that have been traditionally considered part of the Global South have cultivated enough economic and political clout to emerge as regional or global powers, butting heads with one another at times in doing so, subverting the idea of a Global South that is unified and powerless. They have also bypassed traditionally Western-centric multilateral institutions with new groupings like BRICS, and they have found a path toward greater collaboration with the Global North through groups like the G20.

For many governments in the Global South, this improvement in their economic fortunes and political positioning seems to have accelerated rather than dampened their desire for realignment because rising power has not been accompanied by rising privilege. Moreover, not all developing countries have experienced this economic and political empowerment across the board. While some countries that see themselves as belonging to the Global South have seen substantial increases in their wealth and political power, many others have not, remaining trapped in low-income status and locked out of significant multilateral influence. For example, the GDP per capita of Burundi, at $259, is just 3.9 percent of Colombia’s GDP per capita, and just 0.34 percent of the United States’ GDP per capita. Some countries, like India, have seen a significant increase in their global influence, while others remain relatively disempowered.

Additionally, even as many Global South countries mirror each other’s rhetoric in describing the global order, there remain divergences in the positions adopted by individual nations. India and China may both be members of BRICS, but they are intense geopolitical rivals jockeying for leadership of the Global South. Some analysts also speak of a “South of the global South,” a subset of poorer and smaller countries that are subordinated by more powerful countries such as China and India, mirroring the North-South dynamic within the Global South grouping itself.

Given this diversity, invocations of the Global South should focus on one consistent throughline: from the start, the idea was intended to connect myriad experiences with a unifying grievance—a global political economy that perpetuates colonial dynamics and enforces hierarchy—and to advocate for a realignment of the global order to support self-determination.

Conclusion

Echoing decades of political activism, leaders in the Global South are forcefully articulating a desire to realign the global order away from Western dominance. Regardless of whether their perceptions are accurate and whether their grievances are justified, there is no denying the power of this worldview in motivating and justifying political behavior. Refusing to take seriously the core complaints of the Global South risks blinding leaders in the Global North to geopolitical and geoeconomic dynamics that influence actions in the rest of the world and in the process creating a hostile, North-South dynamic.

In addition, if hemming in Chinese and Russian geopolitical influence remains a priority for the United States and the broader West, listening to the demands of the Global South may be strategic, even if that involves ceding moderate control of important global institutions, such as the governance of international financial institutions. Western warnings of Chinese malfeasance in low-income countries on topics such as sovereign debt are often unpersuasive in light of the negative impacts of debt issued by Western or Western-controlled sources. “Condescending” behavior by Western diplomats is already leading to the breakdown of some North-South security partnerships. Refusing to make space at the table and treat all countries as equal partners risks the delegitimization of the Western-led global order.

In acknowledging the importance of the Global South as an idea, actors in the Global North must still recognize that anything done in the name of the Global South may not reflect the desires and interests of all countries within the grouping. Such assumptions risk flattening the agency of Global South actors and prevent the emergence of a more nuanced, respectful, and productive discourse across the North-South divide. Indeed, the diversity of its membership is at the core of the idea of the Global South as a union of countries disempowered in various ways within the international order.

Notes

-

1Carl Oglesby, “After Vietnam, What?,” Commonweal 90, no. 001 (March 21, 1969).

Source link : View Article

Author

-

Erica Hogan is a research assistant in the Carnegie Global Order and Institutions Program. She was previously a James C. Gaither Junior Fellow in the Carnegie Global Order and Institutions Program. Before joining Carnegie, Erica studied Economics and Fundamentals: Issues and Texts at the University of Chicago.